A two-part series focusing on ethical recruitment and how the pandemic is a good catalyst for recalibrating labor recruitment policies

In February this year, the UK government published important changes to a new code of practice that offers guidance on recruiting health and social care personnel from overseas. The goal is to hire more than 50,000 nurses by 2024, and this new code of practice is aiming to achieve that. Previously, there were 152 countries that the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) could not recruit from. With the revisions, the list has been reduced to 47 countries, known as the “red list” countries, which are on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) support and safeguard list.

But more than just bringing in more healthcare workers to the UK, this new code of practice is also aligned with the WHO’s Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel. This set of rules was adopted in 2010 to address the challenges of health worker migration around the world.

The bare bones on ethical recruitment

The WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Personnel was drawn up to discourage 194 member states from recruiting from developing countries that are facing critical shortage in health personnel. At the time the code was developed, 57 countries were experiencing a serious shortage in appropriately trained health workers.

The code also puts an emphasis on equal treatment between migrant health workers and domestically trained healthcare personnel, and achieving health systems’ sustainability, which involves planning, education, and retention strategies to reduce the need to recruit migrant workers.

There are many reasons for the shortage in health personnel. One of these is that healthcare workers are often on the lookout for better opportunities, so they leave their homes in remote areas to transfer to the cities, or they travel abroad. While all countries experience migration of their health workforce, it is worth noting that the ones that suffer the most are those with fragile health systems.

Losing the best, the brightest

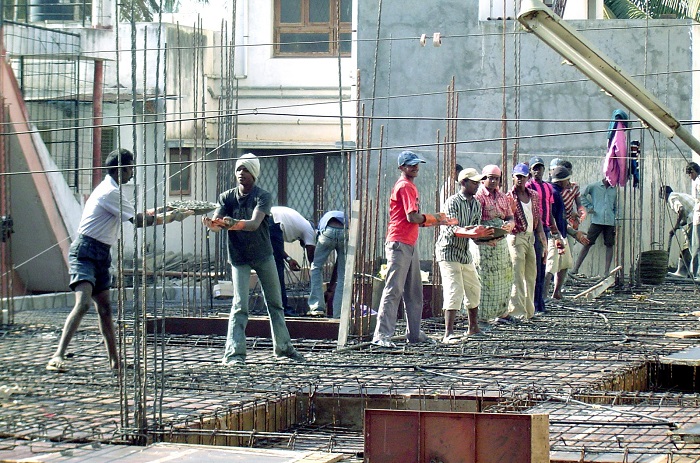

The movement of skilled workers from one area to another, called labor migration, leaves serious effects not just on sending countries but also receiving countries.

Sending countries often experience “brain drain,” which refers to persistent loss of highly trained individuals to other nations. More than the loss of talent, labor migration also translates into huge financial losses for sending states, who had invested time and resources on training their citizens. Certain developing countries like the Philippines support this migration of workers, as it means they are able to send financial remittances back home and help boost the economy.

It’s not just the sending countries that are impacted by this movement of talent. Sometimes migrant workers are often subjected to deskilling, because their education credentials may not always be accepted in receiving countries, or they are given jobs for which they are overqualified, a phenomenon called “brain waste,” which is a loss for both sending and receiving states.

In exceptional cases, migrant workers eventually come back to their home countries, where they are able to apply the skills and knowledge that they developed from their time overseas, a scenario called “brain gain” or “brain circulation.” This is something that both sending and receiving countries should aim for—an equitable exchange for talent.

Wingspan is strongly supportive of the WHO’s ethical recruitment policies and advocates for socially responsible workforce solutions. We aim to promote human capital formation and equitable growth in both sending and receiving countries. The core of what we do focuses on long-term sustainability, and we make sure our recruitment and selection process stays compliant with local and international laws and regulations.

Photo credit by Shilpin Patel

1 thought on “The Impact of the Pandemic on Migrant Workers and How We Can Reform the Labor Recruitment System”

Comments are closed.